How junior engineers become true professionals

When you’re freshly graduated and new in a job, making your way in your profession can be daunting. Finding a mentor who can minimize the fear factor and offer guidance in difficult situations is one of the best steps a junior engineer can take. And the sponsorship program offered by the Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec (OIQ), which grants juniors completing the program the equivalent of eight months’ experience, helps make those connections.

To become full-fledged engineers, junior engineers must pass a professional practice examination and go through a three-year employment period to prove themselves. The sponsorship program, which isn’t mandatory, establishes a formal relationship with a professional engineer. The sponsor and the junior meet six times over at least 15 months, each meeting lasting at least 75 minutes. They discuss 18 topics specified by the OIQ. The sponsor takes no responsibility for the junior’s work, and the topics are not technical; rather, they cover the rights and obligations of engineers and the core values of the profession: competence, ethics, responsibility, and social commitment.

Junior engineers are responsible for finding their sponsors but the OIQ can help the process. For more information, visit www.guidedufuturingenieur.oiq.qc.ca/index.html.

To illustrate the effectiveness of the mentoring program, we present two very recent case studies.

Julie Lefebvre and Robert Bigras

Exploring scenarios and solutions

A junior electrical engineer at Bouthillette Parizeau et Associés, a consulting engineering firm, Julie Lefebvre is winding up her participation in the sponsorship program.

Asked what she expected, Lefebvre responds with a laugh: “I had no idea. When I started, it was really to save time.” But the program quickly revealed its less tangible benefits. The sponsorship became a way “to learn things that you don’t learn at school and on your job. What if a client asks you to do something and you’re not sure whether or not you should? What’s right and what’s wrong?”

Julie Lefebvre, Jr. Eng. Bouthillette Parizeau et Associés

Lefebvre’s sponsor, Robert Bigras, is also her supervisor at work and a project leader. Lefebvre is the third junior engineer he’s sponsored. He does it because of the satisfaction of imparting the knowledge he’s gained: “When I was starting out, the process of sponsoring as it is right now didn’t exist. I missed the structured approach, having specific topics to discuss and learn.” At their lunchtime meetings, “we would discuss a subject and how it affects our work,” Lefebvre says. “We’d give an example of a situation and talk about how to respond to it. Then Robert would say: ‘Well, you know, you also could have done this or that.’”

Lefebvre says that having her supervisor be her sponsor didn’t interfere with the process. “We have a relaxed relationship. It’s a working relationship, but Robert is easy-going, so there’s no pressure if I have a question. He’s always available. He’s my supervisor, but he doesn’t act like he’s The Boss.”

“It was mostly the professional responsibility that we emphasized,” Bigras says. He believes that the most helpful advice he gave to Lefebvre is to listen to the needs of the clients, but within context: “What if the client asked me to do something that is not the best solution—do I have to do it? We have to make sure that we respect the code and the law, to make the client aware of the best solutions.” Lefebvre is pleased with her experience. “I’ve learned how to respond to clients if there’s something that isn’t right,” she says. Discussing hypothetical cases meant that, when similar situations arose later in her job, “I knew what to do before it happened.”

When choosing a sponsor, Lefebvre recommends seeking “someone with a lot of experience and the time to do it, who is open-minded and friendly and who loves to help people.” She also suggests that having more than one junior at a meeting could be a good idea: “It helps to have more subjects and more interaction.” The OIQ permits this type of arrangement as long as each junior fills out a separate meeting report.

Bigras believes that having the sponsor and the junior engineer in the same company is helpful for follow-up, “to make sure that what we discussed is applied every day. With someone from another firm, how can I do that?” He adds: “Even when the sponsorship is finished, the process continues.”

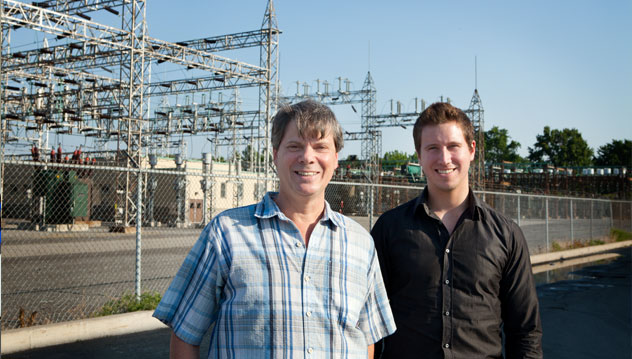

François Moïse and Marc-André Desrosiers

Learning from the voice of experience

François Moïse is a junior electrical engineer at Dessau, a large engineering-construction firm. He wasted no time in seeking out a sponsor, finding one within six months of graduating and starting work. “When you get out of university, you’re usually pretty stressed, starting your first job after school,” he says. “The program is a great opportu-nity to learn from someone.”

He had met the man who would become his sponsor, electrical engineer Marc-André Desrosiers, while doing two summer internships. “Marc-André had been my boss,” says Moïse. “I just called him and asked, ‘Would you like to be my sponsor?’”

Desrosiers, a senior project manager now at MLC Associés, a consulting engineering firm, says he was honoured by the request. Although it was his first sponsorship, he knew what was expected and how he wanted the meetings to go because he himself had had an enthusiastic sponsor. “He was very interested in what I was doing,” Desrosiers recalls. “Once, he even came with me to see the contract I was working on.”

Moïse is very satisfied with the program: “It has been a great opportunity to talk with an engineer about ethical issues I might encounter; for example, what do you do if you realize you’ve made an error in your engineering computation? What kind of solution will you suggest to your client?”

As Desrosiers notes, the purpose of the discussions is to help the junior engineer learn how to be a professional and what kind of attitude to have toward work, colleagues, and clients. For instance, he says, “You might think that it won’t be good for your reputation to admit an error, but sometimes it’s the contrary: You can show yourself as a responsible person, that you want to be sure of the safety of the public. What kind of solution can we find to act as professionals? It’s something that I can give, this kind of vision of how to behave in many situations.” He adds that he also insists on teamwork. “An engineer shouldn’t elaborate a design alone. He must use the skills of everyone around him to test and improve solutions until he ends up with a design as inventive and secure as possible.”

Meetings took place at Desrosiers’ home in the evenings. “We chose each session’s topics together [from the OIQ’s list],” Moïse says. “Marc-André usually started giving some example about his own experience. I’d ask him some questions, and then tell him about one of my experiences. When we were done with the topics given by the OIQ, sometimes we kept talking about other stuff.”

Moïse is pleased that he sought an external sponsor. “It gives you a different point of view,” he explains. Choosing Desrosiers “gave me an opportunity to talk with someone outside my work, so he can give me different advice.”

Their sponsorship period is now drawing to a close, but the men expect to stay in touch. “Because I met Marc-André when I was doing my internship, he was my boss,” Moïse says. “We had a basic professional relationship, but now that we are not working in the same company, you could say it’s more of a friendly relationship.”

“I hope that it will continue,” says Desrosiers. “It’s always interesting to see the evolution of someone’s professional life and personal life.”

Excerpted from Les carrières de l’ingénierie 2013